Neuromuscular Training for Cyclists

What Is Neuromuscular Efficiency

Professional golfers spend countless hours refining their swing. Elite quarterbacks and MLB baseball pitchers alike rigorously work to improve their throwing motion. Olympic speed skaters tirelessly strive to become as aerodynamic and efficient as possible. The small nuances in technique are what separate the good athletes from world-class athletes.

Cycling is no different, yet neuromuscular training is often neglected in many cycling training programs. With the advent of power meters, many cyclists have become consumed with chasing specific power numbers that they give little thought to exactly how they produce that power. This is why neuromuscular training for cycling is essential.

What does neuromuscular mean in cycling? Neuromuscular training, put simply, is training your brain and your muscles to work synchronously and efficiently. To perform a task, your brain recruits specific motor units to contract your muscles. With neuromuscular efficiency, we want your brain to recruit exactly the right motor units at exactly the right time and in the most efficient manner possible. Over time, these small differences in recruitment patterns can make a BIG difference.

Related Reading: How To Become A Pro Cyclist

Why is Neuromuscular Training Important?

In a sport like cycling where competitions often last for many hours, even a few percent difference in performance can be the difference between pack fodder and a race win. The difference between professional cyclists and amateurs is not as clear-cut as you might think. On the surface, one would think those with an extraordinary VO2-max might take the top spot, however, in elite competition VO2-max is not the most important factor in performance.

What is an example of neuromuscular efficiency? In one study, Lucia et. al (2002) compared the results of a VO2-max ramp test in world-class professional cyclists vs. elite amateur cyclists. Both groups had virtually the same VO2-max. However, as intensity increased, the world-class cyclists had a slower rise in VO2-max. At higher intensities, the pros became far more efficient than the amateurs.

Essentially, the pros used less oxygen to achieve the same intensity as the amateurs. Thus, they hit their VO2-max ceiling much later on and completed the VO2-max test at an average of 500w instead of the average 430w in the amateurs. In elite competition, efficiency is a much greater predictor of performance.

To illustrate this point, in separate study by Lucia et. al (2002), an unnamed two-time world champion had a VO2-max of only 70ml/kg/min. This is significantly less than VO2-max values recorded in other top professional cyclists (85ml/kg/min by Edvald Boasson Hagen, for example). Yet he made up for his lower VO2-max with very high efficiency.

After several years of dedicated training, VO2-max reaches a point where it will not improve much further. We must dedicate time to learning how to take our genetically given VO2-max as far as possible by becoming more efficient bike riders.

On the anaerobic side of things, neuromuscular training will help you to become a more explosive rider. You will be able to achieve a higher max power, reach it sooner, and hold it for longer.

In order to be a strong sprinter, you must be able to generate large amounts of force in a small amount of time; this is called Rate of Force Production (RFD). To have a high RFD, an athlete must have a strong “neural drive.” Neural drive essentially describes how strong the connection is between you brain and your muscles and strongly influences your neuromuscular power. Think of it like a Wi-Fi signal, a strong connection means you can do things fast!

Of course, in cycling, the aerobic and anaerobic aspects go hand in hand. If you are more efficient aerobically, you will conserve more energy and be more likely to make the final selection so that you can unleash a beastly sprint at the end. Neuromuscular training will help with all of these things.

See Also: Power Zones For Cycling Endurance Rides

What is Neuromuscular Training for Cycling?

What is the aim of neuromuscular training? Neuromuscular exercises for cycling are about teaching our bodies to recruit muscles as efficiently as possible to produce power. If we recruit extra muscles we don’t need or recruit them at the wrong time, we will consume more oxygen, expend unnecessary energy, and hit our ceiling sooner. Just compare the smooth, quiet pedal stroke of a pro cyclist to that of a newbie cyclist to visualize the difference.

You might think that simply riding your bike a lot will make you a more efficient bike rider. While yes, of course that is true, we must also spend dedicated time teaching ourselves to be efficient. Even if a cyclist rides their bike a lot, if they pedal inefficiently, they are spending a lot of time teaching their body to pedal the wrong way… it might take a lot of work to reverse that muscle memory!

See Also: How to increase anaerobic capacity

How to Do Neuromuscular Exercises

How do you increase neuromuscular efficiency? There are many different ways that cyclists can do neuromuscular exercise. All of them revolve around enhancing the neural pathway to your muscles and teach them to work together to pedal in the most efficient manner.

Oftentimes, cyclists skip these neuromuscular exercises because they seem tedious and they feel as though they aren’t “hard enough” to make them faster. However, these are just as important as your threshold or VO2-max workout. Don’t skip them. These training sessions are taken out of the playbook of some of the best professional cyclists in the world.

See Also: Complete Polarize Training Guide

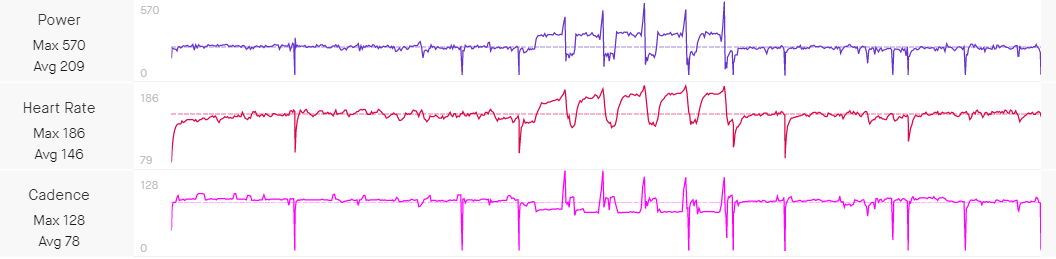

High-Cadence Training: The best track sprinters in the world can sustain up to 200 rpm. These athletes spend tons of time training their neuromuscular systems in the gym and doing neuromuscular workouts on the bike. High cadence training will teach your body to fire muscles rapidly and synchronously and improve neuromuscular fitness.

Additionally, proficiency at high cadence is essential for racing. When you are racing a crit or road race and the pack is flying along at 30 mph, it’s unlikely you will be riding at anything less than 90 rpm. If you tend to grind gears or find it difficult to sustain 100+ rpm without form breaking down, you should dedicate some time to high cadence training.

There are lots of sessions you can do for this. Here are a few examples:

· Spin-Ups: Select a moderate gear, then spin it up as high as possible for 30 seconds. The last 10 seconds, you should be close to the highest cadence you can sustain without form breaking down. The more you do these, the higher cadence you can achieve

· 1-Minuter’s: Perform between 5-10 one-minute intervals between 110-120 rpm at Zone 3 power. Focus on a smooth pedal stroke. Rest for one minute in between.

· Long High Cadence: Select a slightly lower cadence than the 1-minuter’s. Around 100rpm and just ride. Ideal for riding the trainer or flat routes. You can start with intervals of around 5-10 minutes, then extend as you get more comfortable.

Low Cadence Training: Low cadence tempo training requires you to produce greater amounts of force to achieve the same power output and causes you to activate more muscle fibers. By activating a greater number of muscle fibers, you can teach more of them to pedal a bicycle and improve neuromuscular fitness. This is a great way to practice using a full pedal stroke and eliminating dead-spots.

Because they require greater muscle activation, they are also great for improving fatigue resistance. You are more likely to activate your fast fatigable Type IIx muscle fibers and convert them to the more resilient and efficient Type IIa muscle fibers.

Low cadence training is also an excellent complement to a strength training program. We are building lots of new muscle fibers in the gym, particularly Type II fibers. At low cadences, we can activate more of those fibers and transfer strength gains.

Related: What is Neuromuscular Strength Training?

Low Cadence Example:

Old-School Italian SFRs (Salite Forza Resistenza): Sometimes the old-school methodologies just work. Ride in Zone 3 at around 50-60 rpms. Start with doing repeats at 4 minutes and extend as you get stronger.

See Also: Cadence Training For Cycling

Sprints: Sprints are a great neuromuscular power zone workout that help to train neural drive and RFD to teach you to send signals to your muscle fast! There are many different variations that you can do to keep your neuromuscular system on its toes.

Sprint Examples:

· Neuromuscular Power zone Sprints: Select a moderate gear and SNAP as quickly as possible. Achieve the highest power possible for 10 seconds.

· Big Gear Sprints: A fair warning: make sure your chain is not on its last leg with these. Slap it in a big gear and slow down to 5mph, then sprint for 20s while staying in that gear. You’ll be grinding at the start but could reach upwards of 110rpm by the end. You can do these standing or seated.

· Seated Accelerations: Select a moderate gear and, staying seated, spin it up as fast and as hard as you can for 10 seconds. You should be in the neuromuscular power zone for these.

If you want to learn more about anaerobic intervals for cycling, check out our anaerobic bike workouts blog.

Strength Training: In the interest of time, if you want to read more about how strength training can make you a better bike rider, you can read more here.

*Avoid these mistakes if you are beginning strength training

Plyometrics: In addition to strength training, plyometrics are a very effective off-the-bike neuromuscular exercise to improve neuromuscular power. You also don’t need a gym and it takes 10-15 minutes to do them. I really like to incorporate plyometrics more during the season since they aren’t too taxing.

Plyometrics work by training your body’s stretch-shortening cycle. This is almost like a rubber-band effect. When you do an explosive movement, your muscles and tendons store elastic energy, this causes a rebound effect that allows you to produce huge amounts of power. This enhances the brain-to-muscle connection. This is how plyometrics can improve your explosivity and efficiency on the bike when programmed properly.

We can overload your muscles through plyometrics in ways that we can’t on the bike. For example, when doing a jump-squat, you can produce between 2,500-3500 watts (!!) depending on your body size. Think about how much that can improve your neuromuscular power on the bike!

There are two key components to a properly executed plyometric workout: rest intervals and speed. The goal of plyometrics is to produce the most amount of power possible with each repetition.

If your rest periods are too short, you won’t be able to produce as much power. This is similar to a sprint workout on the bike. If you rest 10 minutes between sprints, you’re going to put out a lot more power than if you only rest 10 seconds.

For plyometrics, this means doing no more than six repetitions per set and resting for 3-5 minutes between sets. That’s a long rest period between sets, but it’s the time that it takes for your body to replenish itself so that you can do the most power possible.

During these long rest periods, you can do an upper body exercise to alternate and get more bang-for-your buck. Chest press, rows, and shoulder press are all great upper body exercises that will improve your posture, core strength, and bike handling.

Plyometrics must also be FAST. If you move to slowly or pause in between the movement, that stored elastic-energy will dissipate and you won’t be able to produce as much power

Sample Plyometric Workout:

· Countermovement jump (3 sets of 5 repetitions. 3 minutes rest in between sets). Take 3-5 seconds in between reps to reset.

· Split squat jump (3 sets of 5 repetitions each leg. 3 minutes rest in between sets).

· Single leg squat jump (3 sets of 5 repetitions each leg. 3 minutes rest in between)

*Use rest periods for upper body/core strengthening exercises

See also: Weight Lifting for Cyclists and Core Exercises For Cycling

Neuromuscular Workouts

Neuromuscular training for cycling is the secret sauce to giving you the edge over the competition and should be incorporated regularly into your program. This should become a big focus during your base season because they are not overly taxing and compatible with our focus that time of year. Instead of just cruising around at endurance pace all winter long, by mixing in these workouts, you can get more bang-for-your-buck. In the long run, this will help you to achieve greater fitness when high intensity takes precedence during the season.

Questions? Comments? Coaching? Email the author: Landry@evoq.bike

Author- Landry Bobo

EVOQ Training Plans

Check out our coach built training plans.

References

Haff, G.G. & Triplett, N.T. (Eds.). (2015). Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning: Fourth Edition. Human Kinetics

Lucia, A. Perez, M., Santalla, A., & Chicharro, J. L. (2002). Inverse relationship between VO~ 2~ m~ a~ x and economy/efficiency in world-class cyclists. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 34(12), 2079-2084.

Lucia, A., Hoyos, J., Santalla, A., Pérez, M., & Chicharro, J. L. (2002). Kinetics of VO2 in professional cyclists. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 34(2), 320-325.

Lucia, A., Pardo, J., Durantez, A., Hoyos, J., & Chicharro, J. L. (1998). Physiological differences between professional and elite road cyclists. International journal of sports medicine, 19(05), 342-348.